The Great Usability Recession

#032: My week with "enshitified" technology and what happened to all the unsung usability superheroes.

It started as a feeling, a kind of static in the air around me. Nothing was broken, exactly, but nothing was working quite right either. Well, some things were actually broken, namely my sanity.

Every interaction with a device — my phone, my headphones, my monitor — carried the same faint sense of friction: a click that didn’t register, a prompt that shouldn’t exist, and a feature that solved a problem I didn’t have.

By the end of the week, it felt like I was living inside an omnipresent cloud of broken technology and digital experiences.

My Week with Modern Technology

It began innocently, albeit frustratingly, enough. My AirPods Max, the $550 noise-canceling marvels, refused to pair with my iPhone at the gym for what felt like the 550th time. How I made it through my hour-long lifting session without the Challengers soundtrack is a question to be studied by academics.

Then came the iOS 26 “upgrade,” which left my iPhone 15 Pro Max feeling sluggish and half-responsive. Entire regions of the screen ignored taps and text blurred illegibly into mush under Apple’s new “Liquid Glass” UI. The fact this happened days before my last phone payment was not lost on me.

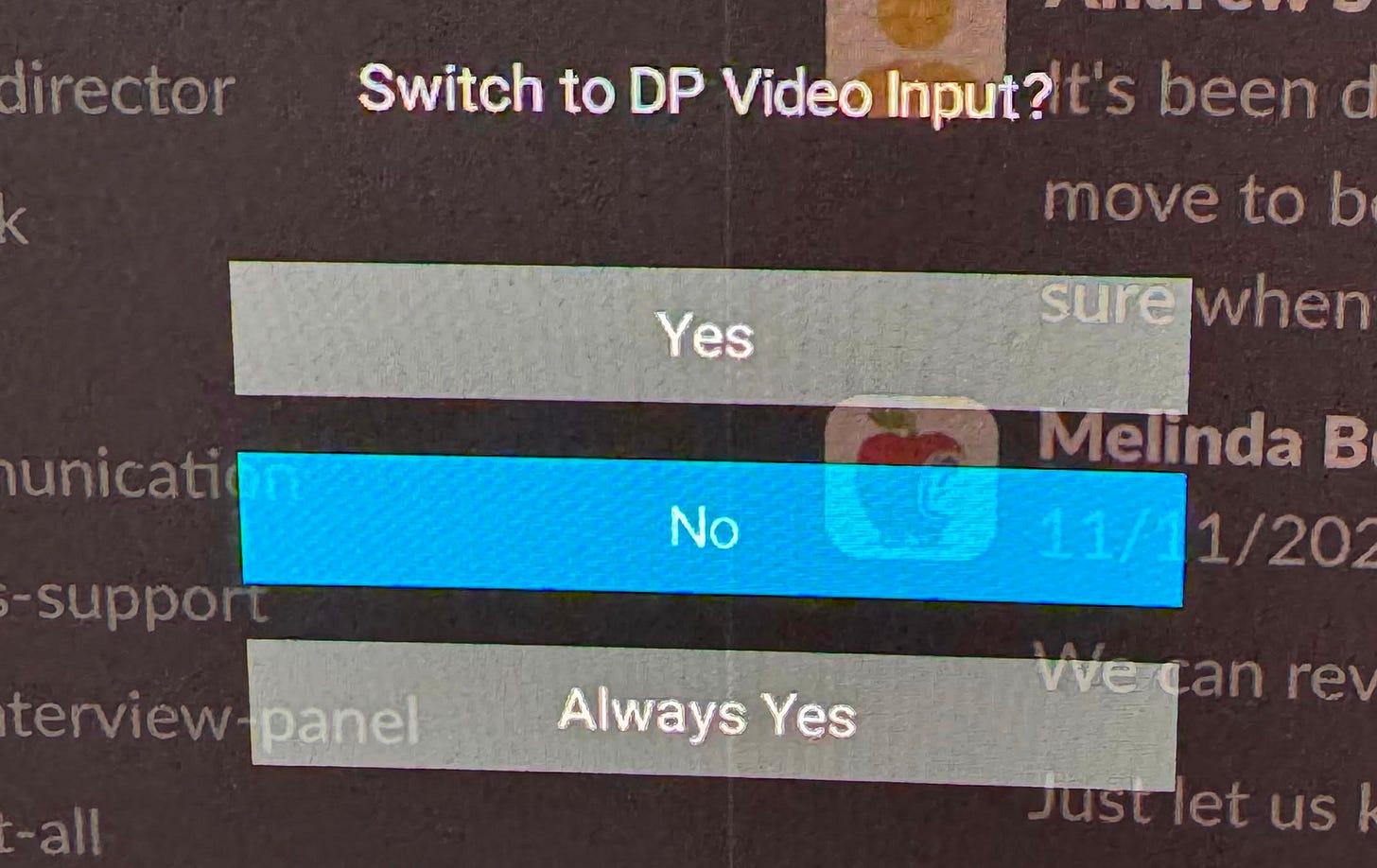

My overpriced OLED monitor joined the rebellion next, asking if I wanted to “switch inputs” every time I accidentally nudged my desk. The pop-up included an “Always Yes” option, but of course, no “Always No.”

At work, we’ve disabled Figma’s AI features — on purpose — yet I was greeted by a cheery “Try AI” prompt on the dashboard anyway. No, I’d prefer to not train the model on my team’s work to the benefit of our competition, thank you very much.

When I open Office 365 to search for a document, I am always greeted by a blank chat window asking if I’d like to “Ask Copilot.” No, I’d like to find my file, thanks. What frustrates me even more is that Copilot is the second navigation option below Search, because Microsoft knows all I want to do is find that file, but they’ve clearly chosen to push their pet AI anyway.

My Smart TV decided I needed to re-pair its own remote, which failed and left the remote effectively bricked.

And to cap it off, the Chicago Sports Network (CHSN) app — which I subscribed to for Bulls and Blackhawks games — played me a silent music note icon instead of the game.

All of this happened in a single week, and it’s not coincidence.

The Death of Baseline Usability

These aren’t edge cases; they’re what happens when companies quietly decide that baseline usability and quality no longer matter.

For years, “usability” meant something simple but profound: it just works. The unsung labor of UX designers, QA testers, and accessibility specialists made sure interactions were reliable, consistent, and human-scaled. That kind of work doesn’t make headlines or shareholder decks, and it doesn’t feed engagement graphs or drive glowing AI demos. So, it’s slowly being erased.

Today, the gravitational pull of modern tech has shifted toward novelty and automation. Every design decision is filtered through engagement metrics, growth OKRs, and “AI integration opportunities.” The result is a digital ecosystem obsessed with appearing intelligent rather than being usable — everything looks smarter, but feels and functions infinitely dumber.

How We Got Here

The subtle shift is that design’s value is increasingly measured by its ability to influence user behavior toward profit-generating outcomes… rather than its ability to make those behaviors intuitive, humane, or equitable.

To understand how we arrived in this mess, you have to rewind a few decades — back to when usability was a science and not an afterthought.

In the mid-20th century, Human Factors Engineering emerged from aerospace and military design, where poorly labeled switches or confusing interfaces could literally cost lives. That discipline — built on psychology, ergonomics, and systems thinking — laid the groundwork for what we now call user experience design.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, those ideas had migrated into the software world. Companies like IBM, Apple, and Microsoft hired human-computer interaction (HCI) specialists, usability engineers, and cognitive scientists to test and refine interfaces before release. “User testing” was standard practice, and “the user” was treated as a real person, not an abstraction.

These roles didn’t exist to make things pretty or drive engagement — they existed to protect usability as a measurable standard of quality.

When something was confusing, it was a defect. When something was slow, it was a bug. And when something failed usability testing, it didn’t ship.

That ecosystem has quietly collapsed.

Today, those once-specialized roles have been absorbed into generalized digital product design tracks, where the incentives are entirely different. Designers are now expected to be “full-stack” — part researcher, part strategist, part conversion optimizer. The metric isn’t usability anymore; it’s performance against growth KPIs.

The subtle shift is that design’s value is increasingly measured by its ability to influence user behavior toward profit-generating outcomes — clicks, conversions, engagement — rather than its ability to make those behaviors intuitive, humane, or equitable. The result is a workforce of talented generalists who are stretched too thin to defend the craft of usability itself.

Meanwhile, others who used to safeguard baseline quality — QA testers, accessibility specialists, and others — have been thinned to the bone or automated out entirely. Their work is invisible by design: when they succeed, nothing happens. No headlines. No engagement spike. Just a product that quietly works. That invisibility made them the first casualties of efficiency mandates and AI optimism, but they were the final line of defense between a functioning system and the chaos we’re starting to live through — the invisible labor of baseline experience acceptability.

Without these disciplines, our digital world has no governor. Bugs become features, annoyances become expectations, and accessibility becomes perpetually “post-MVP”, if considered at all. And somewhere in that fog, the very idea of usability — once the proud, empirical heart of good design — simply drifted away.

The irony is that we didn’t lose usability because it stopped mattering. We lost it because it stopped being visible to those in power. It doesn’t move dashboards or earn headlines, and you can’t A/B test your way into empathy. And so, the very people who made technology livable — the testers, the accessibility advocates, the human-factors engineers — were written out of the story. What’s left are systems that appear more intelligent than ever, yet understand us less with each release.

Re-Centering Usability

This isn’t nostalgia for a simpler time — it’s a plea for accountability. If AI is the next industrial revolution, usability needs to be part of its social contract. Without it, we’re left in a permanent beta test, debugging our own lives.

The truth is that usability was never glamorous. It was the invisible work that made technology humane — the discipline that said “just because it’s possible doesn’t mean it’s good.” Somewhere along the way, that principle stopped fitting neatly into business models.

But it’s not too late to bring it back.

Re-centering usability means putting people — not engagement metrics — at the heart of design again. It means hiring specialists who care about the feel of interaction as much as the flow of revenue. It means treating accessibility, performance, and polish not as polish, but as ethics.

Signal to Watch

Companies that still employ — or promote — dedicated usability specialists will soon stand out not for having the smartest tech, but for having the only tech that reliably works. And that will be a critical business advantage in a world that’s otherwise gone mad with ads that paper over broken experiences.