The Tyranny of Defaults

#025: The choices you never knew you made, by design.

Every time you open a website, you’re asked to “accept cookies.”

Most people click Accept All without a second thought. Not because they want to hand over their data, but because the alternative is buried behind layers of obfuscation: tiny “Manage Settings” links, endless toggles spread across categories with vague labels like Functional or Performance. The design makes the default the path of least resistance — give up your data — while true choice requires exhausting work.

That’s not laziness — it’s human nature. Decision-making is expensive. Every extra click, every extra layer of effort adds friction. And when the cost of making a choice feels high and the benefit uncertain, people tend to accept whatever’s already been chosen for them.

That’s the power and danger of defaults.

The invisible nudge

We’ve seen this across domains:

Organ donation rates soar in countries where the default is “opted in” and plummet where the default is “opted out.”

Retirement savings participation jumped when employers auto-enrolled workers rather than making them sign up.

Facebook privacy settings were once set to share everything publicly by default — few users ever changed them.

iPhone apps like Safari and Apple Maps shaped entire markets by being the default.

Autoplay on YouTube and Netflix keeps people watching, blurring choice into compulsion.

Ride-share tips are nudged upward by preset “suggested” amounts.

Energy programs in some cities default households into renewable plans, dramatically raising green adoption rates.

Defaults aren’t neutral; they tilt the playing field toward what the designer (or policymaker, or corporation) wants to happen. And yet, they remain one of the most invisible forms of design.

Defaults and misunderstanding: the Instagram map

This is the deeper lesson: A default setting isn’t just a toggle, it’s also the mental model people form about what’s happening in the background.

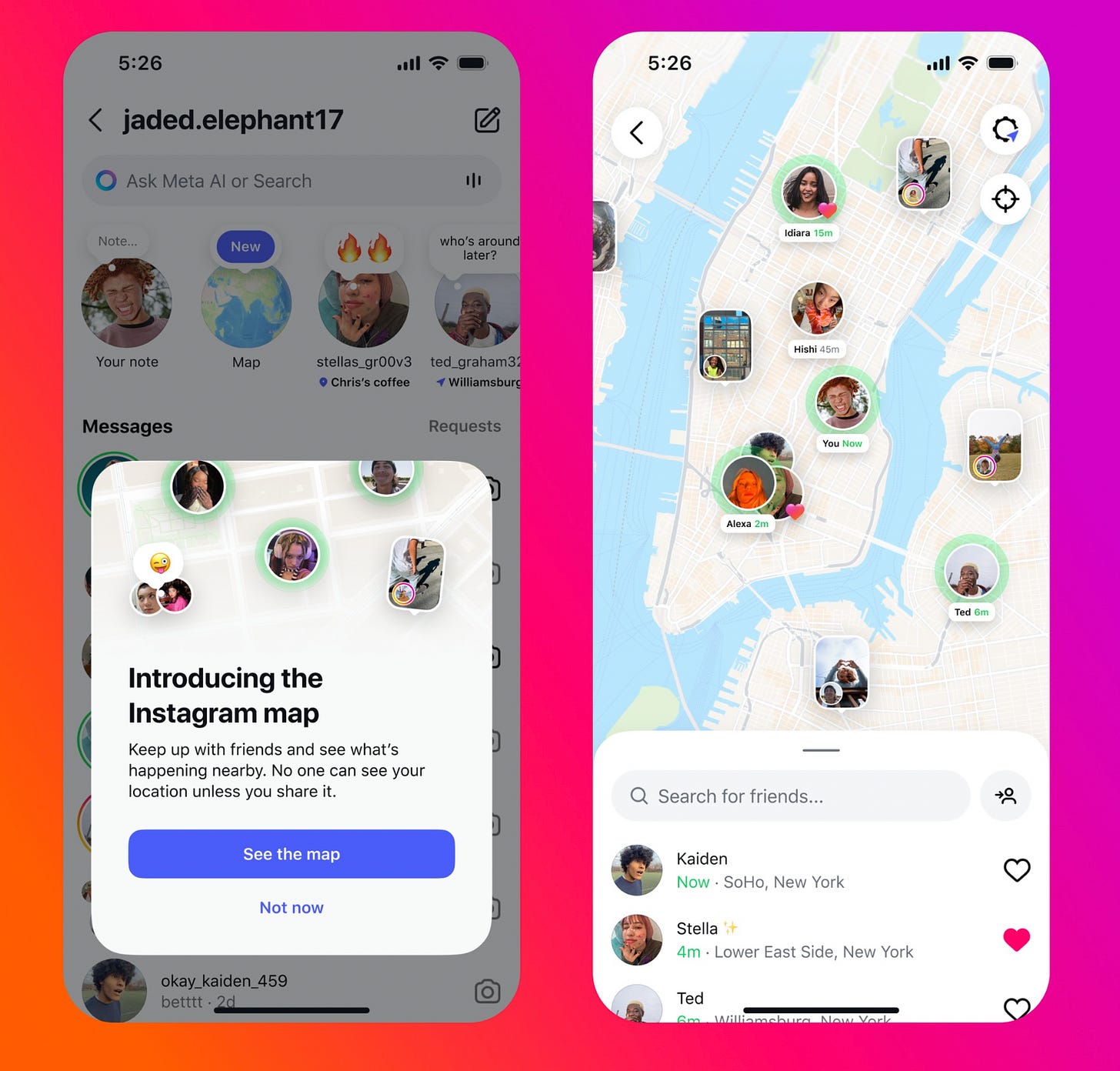

A recent Instagram controversy shows just how messy this can get.

Earlier this summer, Meta launched a new Instagram Map feature. Officially, it was off by default and required a double opt-in for live location sharing. But when users started noticing their location appearing on maps — sometimes even their homes — panic spread.

In reality, many people were seeing a different default at work: when you tag a location in a Story, that tag automatically shows up on the Map for 24 hours. This has been true for years, but users confused it with the new live location feature.

The backlash was swift: Instagram was accused of exposing private data without consent. In response, head of Instagram Adam Mosseri had to clarify that the live sharing feature was off by default, but the confusion remained.

This is the deeper lesson: A default setting isn’t just a toggle, it’s also the mental model people form about what’s happening in the background. If users can’t distinguish between “live tracking” and “geotagged story posts,” then defaults — however technically correct — can feel like betrayal.

Spotify and the iPhone: other defaults gone wrong

Instagram isn’t alone.

Spotify once defaulted new users into sharing their listening activity publicly. Many only discovered it when a friend (or stranger) commented on their playlists. The setting was technically opt-out, but the default framed public sharing as normal.

Apple’s “Frequent Locations” quietly logged users’ most-visited places to improve Siri and Maps. The feature was buried deep in Settings, enabled by default, and largely invisible. When journalists surfaced it, outrage followed — not because the data was inaccurate, but because people didn’t know it was being collected at all.

These cases show how defaults don’t just influence behavior — they shape trust. Even when companies can claim “consent,” users feel blindsided when the design of defaults hides complexity or assumes too much.

Power without accountability

The danger isn’t just manipulation, it’s opacity. Most people never realize they’re being nudged since the default feels like the natural order of things. This means defaults can normalize whatever serves the powerful: surveillance, over-consumption, inequitable access.

Designers are often told to “make it easy.” But easy for who? For the user? Or for the business model?

When Amazon sets “Subscribe & Save” as the default button instead of “One-time purchase,” is that convenience or deceptive coercion?

When Netflix autoplays the next episode, is that generosity or addiction by design?

When Spotify quietly broadcasts your guilty pleasures, or Apple logs your daily commute, is that helpful or a violation of trust?

Rethinking defaults

What would it mean to design defaults with a different ethic?

Defaults that serve long-term well-being instead of short-term clicks.

Defaults that respect autonomy by making alternatives just as easy.

Defaults that can be transparent and auditable, like nutrition labels for choice architecture.

Defaults will always exist. The real question is who they’re designed to serve — and whether we’re willing to make that visible.